Background

The Sultana Shallop (Photo: Chris Cerino)

How It All Started

The Cross Project is an offspring of the 400th anniversary celebration of the founding of Jamestown in 1607. Its origins go back to the Smith shallop project in Chestertown, Md. The Sultana people wanted to build an authentic “Smith” shallop, his “barge of discovery,” as he called it. There were two other shallop projects in Reedville and Deltaville in Virginia, but the Chestertown people wanted to use theirs to reenact Smith’s voyages of exploration using oars and sails (the real thing, no motors).

Where Did Smith Go?

In the fall of 2004, experts gathered to try to determine just what Smith’s Chesapeake route was. The two principal contributors to this effort were Wayne Clark, of the Maryland Historic Trust, professional archaeologist and John Smith historian, and Ed Haile, the poet, a Smith amateur who had arrived on the scene (1995-98) publishing two Smith-related maps and a fat book entitled Jamestown Narratives.

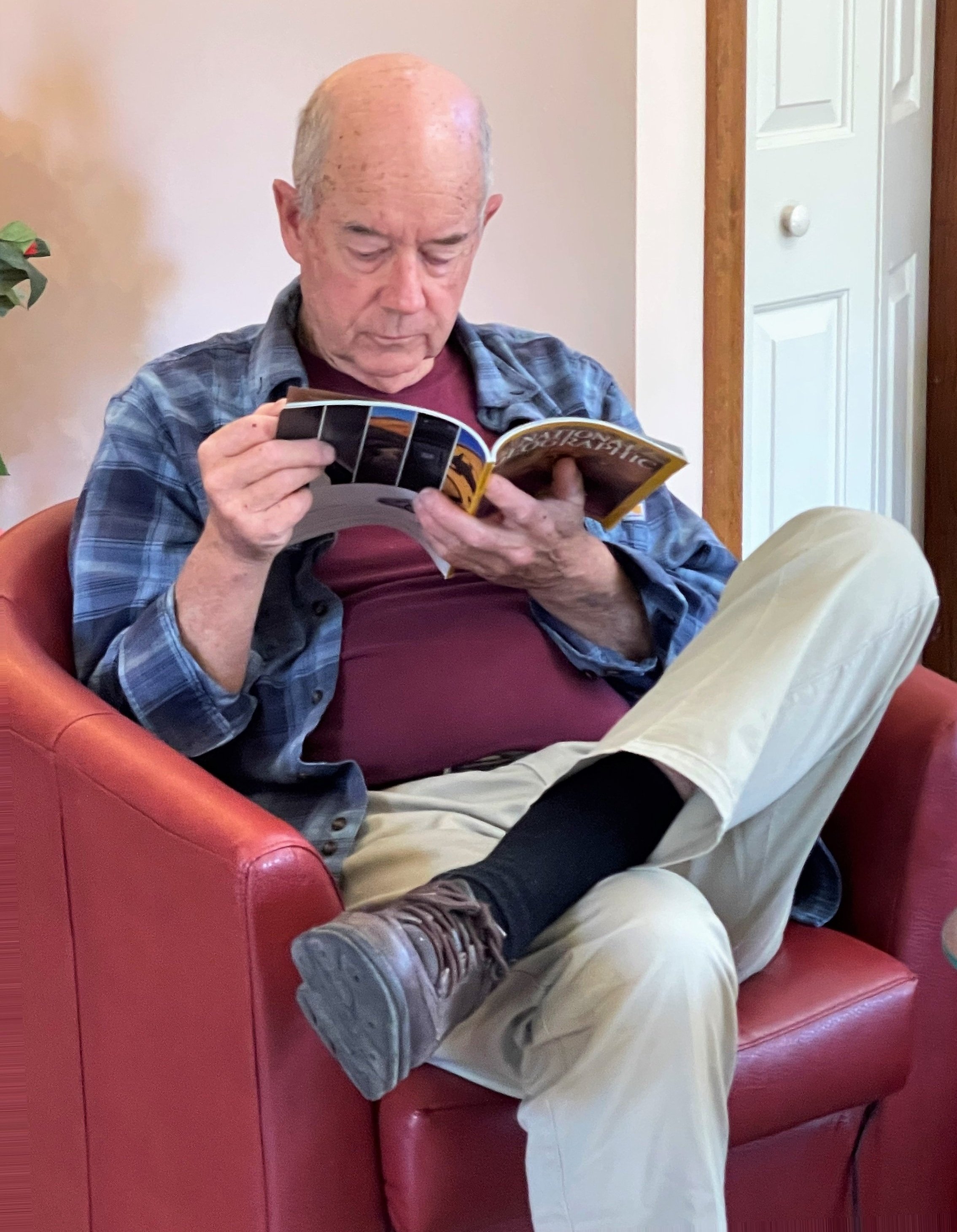

Full Circle: Ed Haile looks back at an article and map in the June 2005 National Geographic, part of an article entitled “Saving the Chesapeake.” The magazine interviewed Ed regarding John Smith’s travels and helped provide information for the map. This article was near the beginning of the cross marker project. Seventeen years later, the project has 21 markers installed across the Chesapeake in Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware as well as a website filled with information about Smith, mostly provided by Haile.

The National Geographic Society published the first draft of that effort and Haile and Clark’s reworking of the Capture Route in its June 2005 issue.

The next thing, with the Smith’s Bay voyages reasonably worked out but for a few details, it was not long before Haile suggested restoring the crosses as a sort of tangible anchor to another suggestion coming out of the celebration, namely the Water Trail idea of a national park.

Everybody, including the National Park Service, the National Geographic, the Sultana Project, the Conservation Fund, the Water Trail lobby in Congress, all of which could be summed up in the person of Pat Noonan, along with most of the history people, told Haile to go to work on it.

A Book or Two

In 2006 they got a book. With a long Jamestown poem. But no, Haile went to work again and they got another book, John Smith in the Chesapeake with the best yet itinerary of all of Smith’s travels in his Jamestown years 1607-09, or as it says in the preface the “how, where, when, and why of the route of the great explorer,” which is everywhere between Smiths Falls, The Falls, Sugar Loaf Mountain, and Cape Henry.

In the back of the book, an appendix lists all 27 Maltese crosses with a general location and the name of each USGS map. Haile and his wife cruised the whole circuit by car, got out and walked around a bit, and had something to say about each location.

The Phone Rang

John Smith in the Chesapeake produced a phone call to Haile from Charlie Stek in February 2009. Stek was president of the Friends of the John Smith Water Trail, forerunner of the present Chesapeake Conservancy, the civilian auxiliary of what was soon to become The Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail.

STEK: “Where exactly are all those crosses?” he asked. “You’ve given a general description: ‘Blands Content, anywhere along the heights overlooking the Patapsco River,’ or ‘Aquia Creek, end of the 250-foot ridge between Garrisonville Road bridge and Cannon Creek.’ Fine, but, Ed, I want you to give us GPS coordinates. We want to put something on the ground.”

HAILE: “Actually, Charlie, I think it’s Cannon Branch. But I don’t have any GPS coordinates. I’d have to …”

STEK: “Don’t worry. If you’ve got some time to spare, I want to send you back out there to get them.”

Encouraging Results

Stek furnished a car and two assistants, Tim Barrett and Jeff Allenby. The first cross team went on a weeklong odyssey. Haile says, “The result was that I was satisfied that given time and some research, Smith’s sites could be recovered. The reason was twofold: the uncanny accuracy of the Smith map, and a wealth of details explicit and implicit in Smith’s text descriptions. When I am asked how it is possible to replace something missing from a terrain of four hundred years ago, I answer that this case is just unique.”

A further encouragement was that so many sites fell in public parks. Markers would amount to one more layer in the historical themes of various county, state, and federal lands that welcomed the public.

Lastly, and chiefly, what emerged and continued to emerge throughout the project was that Smith had really done this. The richness of the 1612 map, distorted from satellite perspective, was intended for eye-level, horizontal perspective of detail, typical among the best of the old maps, once you arrived and looked around down low and close in. The Smith map’s Chesapeake successor, the 1673 Herrman map, is much better from aerial, and very much poorer from horizontal, perspective.

The Cross Project chose to replace Smith’s original brass and carved crosses with pure Georgia gray granite six by six footstones suitably inscribed.

Phase One: Site Determination

The first phase lasted six years. Haile’s chief support and assistance in the effort came from Wayne Clark, Nancy Merrill of the Friends of the Water Trail, Dr. Michael Scott of Salisbury University, John Haynes, base archeologist at USMC Quantico, along with many others including friends and relatives. Certainties of 2007 became the uncertainties of 2009. The certainties of 2009 fell into doubt in 2010, and so on. Some prospective sites were visited a dozen times. At no time was there a signal “proceed to placement” that did not include at least a mild eureka.

Phase Two: Placements

Phase two began in 2015 when Haile received a sponsorship check in the summer from Joel Dunn, head of the Chesapeake Conservancy, successor organization to the Friends. In the fall, Haile invited Jamestown historian and writer Connie Lapallo to join him on the team.

Funds made it possible to design and see to the production of the markers. The granite markers were quarried and shaped in Elberton, Ga., shipped for engraving and storage in Richmond, Va., in January 2016. Funds allowed the team to travel to sites, directly approach parties concerned, conference, consult, rush out to settle last-minute details. In short, funds enabled the flexibility and availability it takes to do 24 projects pretty much simultaneously.

No one on the cross team is salaried, reimbursements are partial, nor has the team hired services beyond the preparation of the markers themselves (highly discounted at each stage). Lodging was our greatest expense.

Phase Three: Independence

As of June 2020, the Project reports to itself. Insofar as some crosses remain to be placed, it can be said that phases one and two continue. We have the same sponsor, now direct, have made the awful and inevitable transition to our own extensive website (entirely prepared by Lapallo), and welcome associate members to come aboard and serve in a guardian capacity to look after a ton of rocks along 698 miles in three states.

All photos: Connie Lapallo